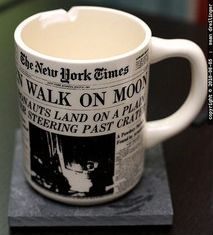

Take a moment to explore your daily newspaper's webpage. You'll likely find recent articles and archives, video materials, job postings, classifieds, sidebars with advertisements, various forms of social media integration, and, most surprisingly (or perhaps not, considering the financial challenges journalism faces), a store. Newspapers including The Los Angeles Times, The New York Times, The Seattle Times, and The Hartford Courant have opened online storefronts that sell page and photo reprints, mugs, t-shirts, and more. One such newspaper used to be the North Adams Transcript, a daily paper in North Adams, Massachusetts that is owned by New England Newspapers. Because of this storefront, they are now defending a lawsuit that raises questions about how to evaluate the newsworthiness defense in privacy cases. In the context of such storefronts, what really matters - content or context?

Take a moment to explore your daily newspaper's webpage. You'll likely find recent articles and archives, video materials, job postings, classifieds, sidebars with advertisements, various forms of social media integration, and, most surprisingly (or perhaps not, considering the financial challenges journalism faces), a store. Newspapers including The Los Angeles Times, The New York Times, The Seattle Times, and The Hartford Courant have opened online storefronts that sell page and photo reprints, mugs, t-shirts, and more. One such newspaper used to be the North Adams Transcript, a daily paper in North Adams, Massachusetts that is owned by New England Newspapers. Because of this storefront, they are now defending a lawsuit that raises questions about how to evaluate the newsworthiness defense in privacy cases. In the context of such storefronts, what really matters - content or context?

During July 2008, Thomas Peckham III was the victim of a drunk driving accident. His photo was taken by a photographer for New England Newspapers at the site of the wreck while he waved to family. This photo appeared as part of North Adams Transcript's coverage of the accident and reproductions of the image were made available on merchandise including "tee-shirts, coffee mugs, and mouse pads." In response, Peckham and his family filed a lawsuit against New England Newspapers, Peckham v. New England Newspapers (Civil Action No. 11-30176-KPN). Peckham alleged a violation of his right to privacy and negligent infliction of emotional distress based on the availability of these products.

New England Newspapers filed a motion to dismiss both claims, asserting that Peckham's complaint was not timely served and raising a blanket defense that the publication of matters of legitimate public concern are protected by the First Amendment. Earlier this June, U.S. Magistrate Judge Kenneth Neiman denied this motion to dismiss, focusing on the photo's newsworthiness as a defense to a privacy right violation. Judge Neiman found that Peckham's complaint could survive the motion to dismiss, because it is possible that this defense would not cover the paper's merchandise sales. Judge Neiman recognized claims under two theories of privacy invasion, the publication of private facts and right of publicity, though Peckham focuses on the former.

As a brief background, Massachusetts recognizes a claim for an "unreasonable, substantial, or serious interference" with one's privacy. A publication of private facts claim requires the following elements be proven: the facts are of a "highly personal or intimate nature" and are of "no business to the public." However, Massachusetts has recognized (in the unrelated case of Peckham v. Boston Herald) an exception to liability when the information publicized is of legitimate public concern (considered "newsworthy").

Massachusetts also recognizes a claim for the unauthorized use of a name, portrait, or picture of a person. Within Massachusetts, this right of publicity aims to protect against unauthorized appropriations of an individual's identity for advertising or trade purposes.

In Peckham v. New England Newspapers, Judge Neiman holds that there is no doubt that the photo is of legitimate public concern, at least in the context of reporting on the accident itself. Accordingly, he does not go into much detail regarding whether there may be a substantial interference with Peckham's privacy from the article in the North Adams Transcript. But because newsworthiness in Judge Neiman's view depends upon not only content, but also the nature of its use, he finds that the same photo might be newsworthy in the context of news reporting but not merchandise sales.

This interpretation of the defense, which the judge applies to both theories of privacy in the case, seems to align more with the right of publicity. Focusing more on the use of the information than the information itself or its source, right of publicity law generally includes protection of an individual's picture from unauthorized advertising or trade use. From this perspective, an interesting right of publicity aspect to Peckham's claim lurks in the background and may have significant implications for these newspaper storefronts.

Of course, addressing Peckham's photo and others in light of a right of publicity is not without its challenges. Where should the line be drawn between protecting the newpaper's speech and the individual's right of publicity? While it may seem simple to distinguish between use of a name or likeness that is purely in the public interest and use that is purely commercial and profitable, there is a whole slew of activity that falls in the middle. A commercial/non-commercial dichotomy may sound ideal, but the difficulties in implementation make it practically useless.

In Massachusetts, the boundary (as interpreted by the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court in Tropeano v. Atlantic Monthly Co., in a manner consistent with some other states) is one in which a defendant cannot use the picture for the intention of profiting from the value of an individual's reputation and identity, though a defendant's "incidental" use of an individual's photo would not be restricted by this doctrine. While this incidental use distinction is better than a commercial versus noncommercial one, it has its limitations in a context like this. As an isolated use, a newspaper may choose to make a photo available for purchase in various forms with no intent or expectation to make a profit from such an accident photo, focusing on a (questionable) purpose of news reporting. (In fact, it is quite possible that no reproductions of the photo of Peckham were sold, though we'll find that out eventually in discovery.)

Clearly, the photo of Peckham is different than a photo with obvious commercial value and marketing potential. For instance, making available an image of the Patriots winning the Super Bowl may suggest a commercial, value-driven intent. However, if the newspaper makes all of its photo archives available for purchase, regardless of their potential commercial value, yet knows that this particular Patriots photo will turn a profit, then does the financial benefit of allowing readers to purchase Patriots' t-shirts become simply incidental to a news reporting purpose? We are then faced with distinctions based not only on purpose or intent, but content once again. It is also impossible not to consider product form when making this distinction - a straight photographic or news page reproduction is one thing, but what about a twenty foot canvas print?

Similarly, while Peckham v. New England Newspapers does not involve a celebrity or public figure, consider the larger implications with photos of popular individuals who make their way into newspapers. For example, The Seattle Times sells create-your-own products (in the same vein as Cafepress and Zazzle) including mugs, mouse pads, puzzles and magnets using images from a gallery of "famous faces" ranging from celebrities like The Beatles and Tom Cruise to President Obama and other world leaders. With just a few minutes of work, I can purchase David Beckham playing cards, a Hilary Clinton button, and a John Lennon t-shirt. These photos were originally published in The Seattle Times in articles of public interest, but I would just be purchasing them as fan merchandise. To me, these products seem to be part of a market for goods more than one of public knowledge or information, and I can't imagine any entity making such merchandise available without intending, or at least knowing, that they could be profitable.

Are all such sales, then, unauthorized unless the newspaper has secured the individual's consent? It is also noteworthy to see that North Adam Transcript's store is no longer available during this case, and I personally don't anticipate its return anytime soon. In the meanwhile, as Peckham proceeds, we will hopefully get answers to at least some of these questions from the District Court for the District of Massachusetts.

Kristin Bergman is an intern at the Digital Media Law Project and a rising 2L at William & Mary Law School. If The Seattle Times featured Sandra Day O'Connor in their Famous Faces gallery, she would now be the proud owner of a new button.

(Image courtesy of Flickr user sean dreilinger, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 license)